Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

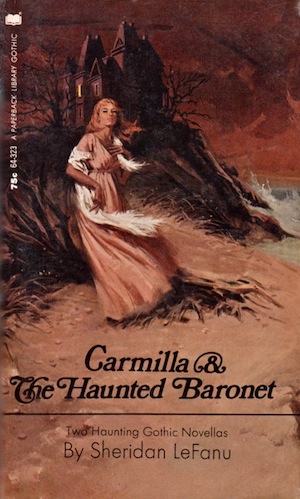

This week, we continue with J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, first published as a serial in The Dark Blue from 1871 to 1872, with Chapters 5-6. Spoilers ahead!

“Let us look again for a moment; it is the last time, perhaps, I shall see the moonlight with you.”

Laura and her father inherited a number of paintings from Laura’s Hungarian mother. As “the smoke and dust of time had all but obliterated them,” they’ve been with a picture cleaner in Gratz, whose son now arrives with a cartload of restored artwork. The whole castle gathers to watch them being unpacked. Nearly all the paintings are portraits; Laura’s father is particularly interested in one of a “Marcia Karnstein,” dated 1698, so blackened before that its subject was invisible.

The canvas now is vividly beautiful, and Laura is amazed to see in it the exact likeness of Carmilla, down to the mole on her throat. Her father is too busy with the restorer to take much notice, but gives Laura permission to hang the portrait in her own room. Carmilla, however, smiles at Laura “in a kind of rapture.” The name inscribed in gold on the portrait, now fully legible, reads not “Marcia” but “Mircalla, Countess Karnstein.” Laura remarks that she herself is descended from the Karnsteins on her mother’s side. So, says Carmilla, is she–it’s an ancient family. Laura’s heard the Karnsteins were ruined long ago in civil wars, but the remains of their castle stand just three miles away.

Carmilla invites Laura to take a walk on the beach in the moonlight. It’s so brilliant, Laura says, that it reminds her of the night Carmilla came to them. Carmilla’s pleased Laura remembers that night, and that Laura’s delighted she came, and that Laura has claimed the look-alike portrait for her own. She clings to and kisses Laura. How romantic Carmilla is! Laura’s sure her story, when finally told, will feature some great romance still ongoing. But Carmilla says she’s never been in love, nor ever will be unless it’s with Laura. Her cheek, pressed to Laura’s, seems to glow. “I live in you,” she murmurs, “and you would die for me, I love you so.”

Laura starts away, to see Carmilla’s face grown colorless. Claiming she’s chilled, Carmilla urges a return to the castle. Laura presses her to speak up if she’s really ill; her father is worried about the strange epidemic of expiring young women in the neighborhood. Carmilla, however, has already recovered, for there is never anything wrong with her beyond her chronic languidness.

Later that same night, Laura’s father asks Carmilla if she’s heard from her mother or knows where she can be reached. When Carmilla offers to leave, fearing she’s imposed too much on her kind hosts, he quickly explains he only wanted to ascertain what her mother might wish for Carmilla, considering the epidemic. Indeed, he and Laura cannot spare her.

The girls retire to Carmilla’s room for their usual goodnight chat. Carmilla reverts to her strange, even alarmingly ardent mood. Soon she will be able to confide all to Laura. Laura will think her cruel and selfish, but then love is selfish. Laura, she says, “must come with me, loving me, to death; or else hate me and still come with me, and hating me through death and after.”

Buy the Book

And Then I Woke Up

Must Carmilla talk her “wild nonsense” again, asks the embarrassed Laura. No, instead Carmilla relates the story of her own first ball, the memory of which has been dimmed by an attempt on her life later that night. Yes, she came near dying from the wound to her breast, but “love will have its sacrifices. No sacrifices without blood.”

Laura creeps off to her own room “with an uncomfortable sensation.” It strikes her that she’s never seen Carmilla at prayer, though Carmilla says she was baptized. Having caught the habit from Carmilla, she locks her door and searches the room for intruders before getting into bed. As it has since her childhood, a single candle holds off full darkness.

She sleeps and dreams that a “sooty-black animal” resembling “an enormous cat” has somehow invaded her room to pace back at the foot of the bed. As its pace quickens, the darkness grows until Laura can see only its eyes. The beast then springs onto the bed, and two large needles seem to dart into Laura’s breast!

She wakes screaming. Her single candle illuminates a female figure at the foot of the bed, clad in a dark loose dress, hair streaming down. It stands still as stone, not breathing. As Laura watches, it changes place to nearer the door, then beside the door, which opens to let it pass outside.

Laura can at last move and breathe. She supposes she forgot to lock her door, and Carmilla has played her a trick. However, she finds the lock secure. Afraid to open the door and look into the hall, she returns to bed, hides under the covers, and “lies there more dead than alive till morning.”

This Week’s Metrics

By These Signs Shall You Know Her: Carmilla never prays, and indeed avoids other people praying. Laura does admit that if she “had known the world better,” she wouldn’t have been quite so surprised by this casual irreligiosity. By Carmilla’s apparent ability to walk through locked doors and turn into a giant cat, however…

What’s Cyclopean: “Languid,” as mentioned above, is the word of the day and possibly the word of the century.

Anne’s Commentary

Apparently it’s not all that uncommon in Real Life for people to happen upon old portraits whose subjects resemble them to an uncanny degree. Have a look at a bunch of these “doppelgaenger portraits” at boredpanda.com! You could say that there are only so many combinations of human features to go around, so resemblances across time and space are sure to appear. You could posit that the modern person and the historical subject are more or less distantly related. You could shrug that the “meeting” of the doppelgangers is sheer coincidence and/or wishful thinking on the part of the viewer. Or if you wanted to be more interesting, you could speculate that the living person is a time traveler, or the dead subject reborn, or that the subject is an actual ancestor whose evil personality may infect his descendent via some magic intermixed with the paint.

All of the above are common fictional tropes involving portraits. One of my favorite examples is the portrait of Joseph Curwen in Lovecraft’s Case of Charles Dexter Ward. As with Mircalla’s portrait, it takes the labors of a restorer to reveal its subject, at which time Charles gapes in wonder at his notorious ancestor’s close–no, practically identical!–resemblance to himself. The only difference, apart from Curwen’s greater age, is that he has a scar on his brow. Mircalla outdoes Curwen in the doppelgaenger-portrait contest in that she and Carmilla are the same apparent age and have identical moles on their throats. Sometimes the viewer of the doppelgaenger portrait doesn’t know the subject is their ancestor; typically, this relationship bursts upon them later as a climactic shock. This isn’t the case in Carmilla: Carmilla is aware (as well she may be) that she has Karnstein ancestors, and so the uncanny resemblance has a natural explanation. The supernatural explanation will come later: Carmilla is a time traveler of sorts, in that she and Mircalla are the same person, persisting unaged through the centuries by virtue of her undead condition.

That Laura’s family possesses Mircalla’s portrait would be a stretch of a coincidence except that Laura is also related to the Karnsteins through her Hungarian mother. The mother with Karnstein ancestors would be another stretch of a coincidence except that it’s actually an intriguing plot-thickener. We already knew there was a prior connection between Laura and Carmilla–Carmilla appeared to child-Laura in a dream, except maybe it wasn’t a dream after all. Maybe the “dream” was Carmilla’s first visit to her long-lost cousin. They share the same blood, and doesn’t blood call to blood? Could Laura’s Karnstein-kinship be the reason Carmilla has sought her out, an explanation at least in part for Carmilla’s ardent affection for this particular victim? Other young women of the neighborhood are just meals to Carmilla, fast food to sustain her on the road to the superlative feast of Laura.

A gourmet can subsist on fast food only so long, especially when the exquisite feast is always laid out before her, as it were, ahem, nudge nudge say no more. And so in the next chapter, Le Fanu finally abandons foreplay and gets down to business.

Though Carmilla’s lapses into “wild nonsense” have always confused and repulsed Laura, Carmilla has been able to pass them off as mere “whims and fancies” and to recloak her aggression in passive languor. Even so, Laura’s keyed up, subconsciously aware she’s being stalked; hence she’s adopted Carmilla’s bedtime ritual of checking for “lurking assassins” and locking her door. Dreams, however, “laugh at locksmiths.” What Laura dreams this night is that a beast as big and sooty-black as a panther is pacing at the foot of her bed. The beast springs on her bed and drives two needle-sharp fangs into her breast–at last comes the deflowering penetration foretold in Laura’s childhood vision. She wakes up to see a female figure at the foot of the bed, stone-still and with no visible “stir of respiration.” Nightmare has become reality. Or has it? The figure moves in strangely disjointed “changes” of place, seeming to open the door in order to exit, but when Laura checks, the door is locked as she left it before retiring.

Now this is cruel. Unless Laura has the guts to throw open the door and search for the female intruder, she has to remain uncertain. Her guts aren’t that ballsy. Would any of ours be, or would we too huddle back under the covers “more dead than alive”?

Alternatively, and with less bodily if not less psychic risk, we could check our breasts for two puncture wounds and the blood surely to be streaming from them. By “breast,” by the way, I take it Le Fanu means the upper chest rather than the feminine glandular organ. [RE: I was honestly imagining this like a vampiric biopsy needle. Ow.] “Breast” remains more suggestive than “throat,” however. Could this be why Carmilla doesn’t just go for the jugular like your standard vampire?

As far as the text of the chapter tells us, Laura has neither wounds nor bloodied nightgown and sheets to ponder. Could Carmilla’s form of vampirism leave no such incriminating evidence? Or could she not quite have consummated her desire on this nocturnal visit?

The tease must continue at least until the next chapter…

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Languid. Languidness. Languidge? Languidity? Aside from beauty and tell-don’t-show charm, it seems to be Carmilla’s most notable characteristic. It’s an exact choice of word, hovering on the border between positive and negative connotation. To be languid is to lack energy—but to do so gracefully, like someone dying in a romantic poem or perhaps just suffering from chronic anemia. It isn’t to move at all like a 3-year-old, if you’ve ever met a 3-year-old, but we’ll let that pass as we’d really prefer to keep our toddlers far away from Carmilla.

She was, presumably, less languid as a mortal teenager. We learn this week that she was turned into a vampire (or at least started the process) at her first ball, which may explain why she has all the control over her emotions of an extremely hormonal 16-year-old. Imagine if Anakin Skywalker had met Dracula instead of a Sith Lord. Inconveniently—but unsurprisingly if she was being trotted out as a potential bride—she got her portrait done just before she stopped aging forever, and her portraitist was talented enough to capture all the little details. (That the last scion of the bloodline got vamped also perhaps explains what happened to the Karnsteins.) Carmilla manages a good poker face when said portrait gets unboxed in front of her, but she may be expecting it—Laura’s Karnstein blood presumably being part of what drew her here in the first place. Indeed, she seems more pleased than alarmed by Laura’s interest in it—and therefore presumably in her.

That’s probably why the portrait touches off yet another round of creepy drunk texting. The rule, Cara honey, is that if you sound like Lord Byron, you need to lay off the seduction for a while even if it’s working. Put down the phone, stop telling people how lovely it is that they’re going to die for you, and think about the importance of distinguishing love from hate and not just passion from apathy. No, actually, it’s Laura that I want to pull aside for a serious talk about restraining orders. But she doesn’t have anything with which to compare Carmilla’s behavior, which is her problem in the first place. And her father provides no warning cues—we had a discussion in the comments a couple of weeks ago about the implications of this whole business for his character.

He even has a perfectly nice opportunity to kick the scary stalker out of his house, when Carmilla suggests that she ought to leave. She’s obviously playing for the outcome she gets, but it is a chance to forestall the whole plot with no violation of hospitality. But Carmilla makes his daughter so happy…

Modern sexy vampires have some advantages: not just beauty, but often the ability to enthrall victims, and bites as pleasurable as they are painful and dangerous. Carmilla doesn’t benefit from these newfangled developments: her bite is a bite. It hurts and it’s scary, and it tends to wake people up. Her wanna-be dentist described her teeth as needle-like, and they appear to be inconveniently large-gauge. [ETA: Though as Anne points out, they may have the advantage of not leaving marks.] I’m not sure where turning into a giant cat helps mitigate this, other than by convincing victims that they’re dreaming. On the other hand, if I could turn into a giant cat I would definitely do so even when it was inconvenient. On that, Carmilla and I are entirely on the same page.

Still—girl, put down that phone until you’re feeling better. And Laura, sweetie, you’ll be a lot happier if you block that number.

Next week, we explore a different take on vampires in Erica Ruppert’s “The Golden Hour.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden comes out in July 2022. She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.